Opal is a stone that sparks strong reactions. Some people call it lucky and carry it as a talisman. Others avoid it, convinced it brings misfortune. The split response isn’t random. It comes from a mix of the gem’s physical fragility, the way its colors change, and centuries of stories that attach moral meaning to that change. To understand why opal is loved in some cultures and feared in others, you need both the science and the myths behind it.

What opal actually is — and why it behaves oddly

Opal is hydrated amorphous silica. Chemically it is written SiO2·nH2O. That “nH2O” matters: opal contains water, typically 3–21% by weight (most gem-quality opals are around 6–10%). The water and the disordered silica structure make opal softer and more vulnerable than quartz. On the Mohs scale opal ranks about 5.5–6.5. That means it scratches more easily and can craze (develop a network of tiny cracks) if it dries or is heated too quickly.

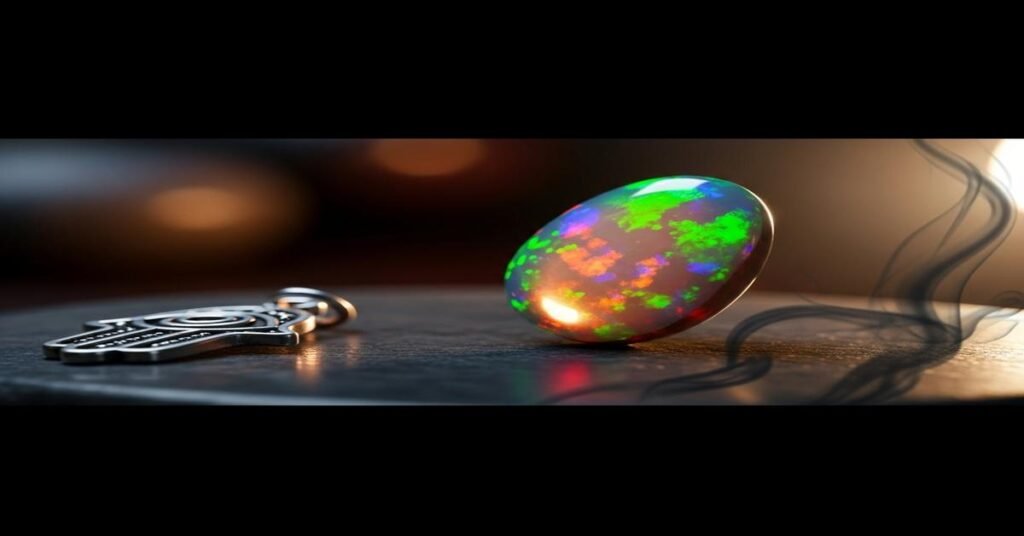

Opal’s famous play-of-color — the flashes of red, green, blue and every shade between — comes from tiny, regularly packed silica spheres in the stone. Those spheres are roughly 150–300 nanometers across. Light diffracts through the gaps between spheres and separates into color bands. Because the effect depends on viewing angle, lighting and sphere arrangement, an opal can look dramatically different from one moment to the next.

How science created superstition

Two physical facts help explain the fearful stories. First, opals can change their appearance or even crack under rough conditions. A jewel that suddenly dulls or fractures is easy to read as an omen. People in pre-modern societies often interpreted sudden changes in treasured objects as signs from the divine.

Second, opal’s color-shifting makes it look alive. A gem that seems to move or flash like fire invites projection: if it shines brilliantly, it might be “good”; if it goes cloudy, people will fear a loss of favor. The tendency to read meaning into change is human. Over centuries that tendency became rooted as cultural lore.

Fear of opal: where it comes from

- Medieval and Renaissance Europe — In earlier periods opal was actually prized for its supposed combination of all gem virtues. Later, however, ambiguous stories spread that opal could bring bad luck if mishandled. The unpredictability of the stone reinforced those tales.

- 19th century literary panic — A specific turning point was the 1829 novel Anne of Geierstein by Sir Walter Scott. In the book an opal loses its fire and disaster follows. Novels shaped fashion and belief then; the book helped create, or at least amplify, the “opals are unlucky” idea in Europe. People like simple cause-and-effect stories, and a novel offered one.

- Misunderstanding of physical changes — When opals crazed after being mounted, heated, or dried, observers who didn’t know the chemistry assumed a moral or supernatural reason. That reinforced fear across generations.

Why other cultures revere opal — protection, healing and sacred stories

Elsewhere, opal’s shifting light became a sign of spiritual power rather than danger.

- Australian Aboriginal cultures — Several groups tell Dreamtime stories that link opal to the rainbow, creation and the spiritual world. In these tales opal contains spiritual light or the footprint of a creator-being. That sacred quality makes opal protective and healing. The stone is treated with reverence, not fear.

- Ancient Rome and Greece — Pliny the Elder praised opal for combining the best colors of other gems. Romans prized it for beauty and believed it could grant foresight or protection. The logic: a stone that contains many colors embodies powers from many stones, so it protects and enhances multiple virtues.

- Folklore and eye protection — Across parts of Europe, opal was associated with eyesight. Because its color play is related to light and vision, it was used as an amulet against eye diseases and the evil eye. In other words, the stone’s optical properties suggested a natural link to vision and therefore to protective uses.

Practical reasons behind talisman use

There is also a practical angle. A soft or fragile stone worn close to the body signals careful handling. If you wear an opal and treat it gently, you will avoid injury and misfortune that comes from reckless behavior. Over time this sensible habit becomes encoded as “the stone protects you.” So some protective beliefs may reflect the social effect of prudent behavior encouraged by the stone’s fragility.

Modern context — gem trade, treatments and perceptions

Two developments changed opal’s cultural standing in the modern era. First, large deposits were found in Australia in the 19th century, turning opal into a widely available gem. Second, gem-cutting and treatments evolved. Thin natural opal slices are often made into doublets or triplets to stabilize them. A typical doublet is a thin opal layer (sometimes 0.3–1.0 mm) glued to a dark backing to enhance color. A triplet adds a protective cap of ~0.5–1.0 mm quartz or glass. These constructions reduce the chance of cracking and make the color more durable, which reduces superstitious fear because the stone behaves more predictably.

How to use opal as a protective amulet — practical tips

- Choose the right cut: solid opal cabochons (e.g., a 1 ct stone often about 7×5 mm) are best if you want a long-term talisman. Doublets and triplets are fine for costume or occasional wear but need more care.

- Set wisely: bezel settings protect the edges and reduce knocks. Avoid exposed prong settings for soft stones.

- Avoid heat and rapid drying: opal can craze if heated quickly. Don’t store it in hot cars or expose it to strong heat sources.

- Cleaning: use mild soap and water. Do not use ultrasonic cleaners or steam cleaners, especially on doublets and triplets.

- Storage: to prevent drying, you can store opal with a small piece of damp cotton in a sealed bag for long-term storage, especially for older or fragile stones.

Conclusion

Opal’s split reputation is not mystical coincidence. It comes from the stone’s chemistry, its shifting light, and human ways of making meaning. In cultures that value the rainbow and the living quality of light, opal becomes sacred and protective. In cultures that read sudden change as a warning, opal becomes suspect. Today, better gem-cutting and clearer knowledge of opal’s needs mean most fears are practical rather than supernatural. If you respect the material limits of opal and choose appropriate settings, it can serve both as a beautiful jewel and a meaningful talisman.

I am G S Sachin, a gemologist with a Diploma in Polished Diamond Grading from KGK Academy, Jaipur. I love writing about jewelry, gems, and diamonds, and I share simple, honest reviews and easy buying tips on JewellersReviews.com to help you choose pieces you’ll love with confidence.