Paraíba Tourmaline or Treated Blue? 3 Quick Checks Before You Pay

Paraíba tourmaline is prized for a neon, almost electric blue-green that comes from trace copper (Cu) and sometimes manganese (Mn) in the crystal. That color is rare and expensive. Many stones marketed as “Paraíba” or “Paraíba-like” have been color-enhanced or never contained copper at all. Below are three fast, practical checks you can do in a store or before you buy online. Each check explains why it matters and what a red flag looks like.

1) Ask for a reputable lab report — and read it

- Why: You cannot reliably tell copper content or geographic origin by eye. Labs use instruments such as LA‑ICP‑MS (laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry) to measure trace elements. These tests show whether copper is present and whether the stone is natural or treated.

- What to request: A report from GIA, AGL, SSEF, or another recognized lab. The report should list trace elements (Cu, Mn) and state whether color is natural or due to treatment. If the word “treated” or “irradiated” appears, ask for details.

- Red flags: No report for a high‑value stone, a report from an unknown lab, or a report that only gives descriptive terms (e.g., “vivid blue”) without trace element data. A seller who resists an independent report is suspect.

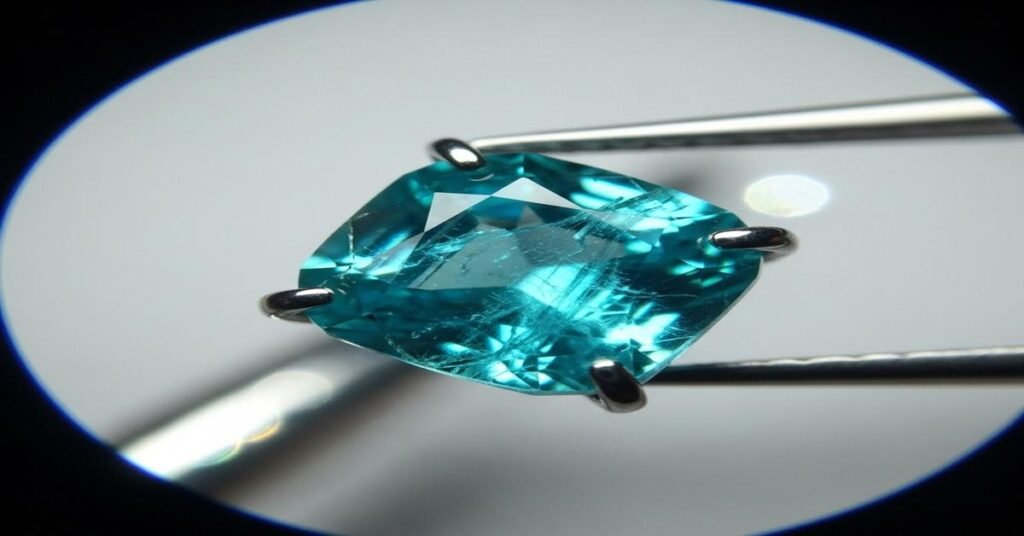

2) Do a simple visual / loupe inspection — look for fillings and telltale inclusions

- Why: Treated or simulated stones often show different internal features than natural Cu‑bearing tourmaline. Glass fills, surface coatings, or dyed fractures leave visible clues under 10× magnification.

- How to check: Use a 10× loupe and bright white light. Rotate the stone and look for:

- Thin, glassy flash lines or “flow” within fractures. These look like bright, reflective films and suggest glass filling.

- Air bubbles trapped in healed fractures. Rounded bubbles in fracture planes usually indicate glass or resin that was added.

- Color concentrations along cracks or sanding marks near facets. Surface coatings or dye often collect in nicks and appear darker.

- Natural inclusions typical of tourmaline — needlelike (rutile), liquid‑gas “three‑phase” inclusions, and parallel growth tubes. These point to an untreated natural crystal.

- Red flags: Flashy, mirror‑like patches inside fractures; perfectly rounded bubbles; color that looks concentrated only along cracks or the surface.

3) Check optical and specific gravity clues — quick equipment tests

- Why: Tourmaline has characteristic optical properties. Some imitations or heavily treated pieces will fall outside these ranges.

- Tests you can ask for or do if tools are available:

- Refractometer: Tourmaline is singly refractive to weakly birefringent. Typical RIs: nω ≈ 1.644 and nε ≈ 1.624 (commonly reported range 1.624–1.644). If the stone’s RIs are far outside this range, it may not be tourmaline or could be coated.

- Polariscope / pleochroism: Tourmaline shows strong pleochroism. Rotate the stone: a Paraíba‑type tourmaline often shifts between bluish, greenish, and slightly violet tones depending on orientation. Little or no pleochroism can indicate glass or certain synthetics.

- Specific gravity (SG): Tourmaline SG is about 3.06 (roughly 2.9–3.2 depending on composition). A much lighter or heavier reading suggests a different material or heavy filling.

- Strong incandescent vs daylight check: View the stone in daylight (or 6500K lamp) and under warm incandescent light (2700K). Natural Cu‑bearing tourmalines maintain vivid color in both lights, though they may appear greener in daylight and bluer under warm light. If the color collapses or becomes uneven, suspect treatment/coating/dye.

- Red flags: RIs outside the tourmaline range, no pleochroism, SG far from ~3.06, or color that disappears under one light source.

Deeper background — why this matters

The unique neon of Paraíba tourmaline is not just hue but chemistry. Trace copper (Cu) is the main cause. Heat treatment cannot introduce copper into a stone; it can only change color when the element is already present. That means a true Cu‑bearing tourmaline with natural color should test positive for copper. Some stones are labeled “Paraíba” because they look similar, but they come from Mozambique or Nigeria or are simply other blue tourmalines. Those can be attractive but are priced differently. Others have been altered: surface coatings, dye, glass filling, or even painted facets produce a vivid color but lower durability and resale value.

Practical buying tips

- Insist on a lab report for any piece over a modest price. Even small Paraíba‑type stones command a premium when proven natural and untreated.

- Get the seller to disclose treatments in writing. If they say “heated” or “treated,” ask for specifics and a supporting report.

- Compare similar stones. A 1.0 ct vivid, neon‑blue piece from Brazil should be priced far higher than a similar‑looking stone without origin or trace element data. If the price gap is small, ask why.

- Ask about setting and wear. Glass‑filled or coated stones can be damaged by heat and chemicals during jewelry setting or repair. A jeweler should avoid soldering close to a filled stone.

- If you buy online, require a full refund policy and a clear, independent lab report. High‑resolution photos from multiple angles under daylight and incandescent light help.

Final note: A fast in‑store check can flag many problems, but it does not replace laboratory testing. If you’re paying fine‑jewelry money for a Paraíba color, budget for a trusted lab report. That report is the only reliable way to confirm copper content and whether the color is natural. It is the single best protection for your purchase.

I am G S Sachin, a gemologist with a Diploma in Polished Diamond Grading from KGK Academy, Jaipur. I love writing about jewelry, gems, and diamonds, and I share simple, honest reviews and easy buying tips on JewellersReviews.com to help you choose pieces you’ll love with confidence.