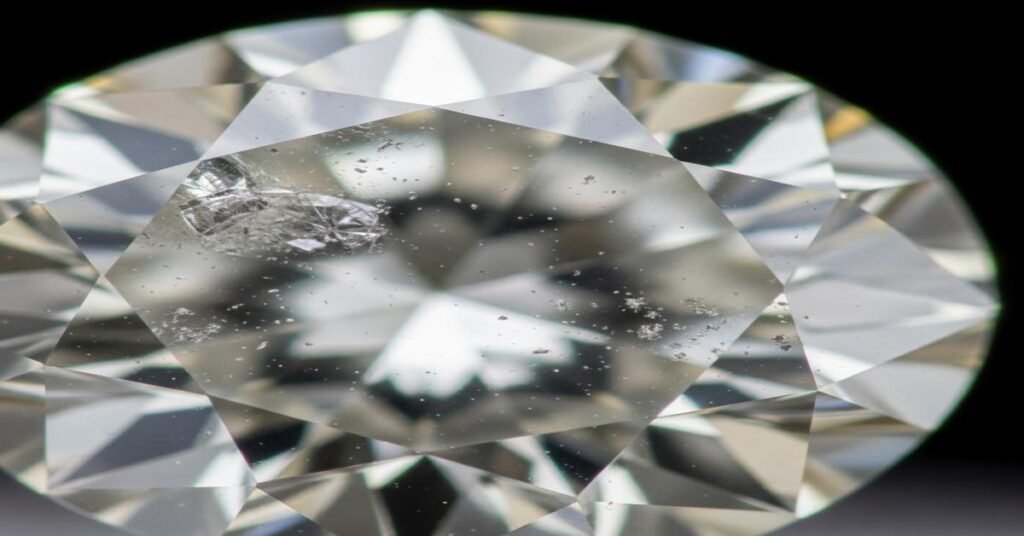

Ask any bench gemologist: if you know what to look for, the inclusions inside a diamond read like a travel diary. Natural stones carry the scars and hitchhikers of violent geological growth. HPHT and CVD lab diamonds, grown in tidy machines, tend to be orderly—sometimes suspiciously so. Below, I’ll show you the inclusion patterns that most reliably separate mined diamonds from HPHT and CVD synthetics, and explain exactly why those features form.

Why inclusions separate natural from lab-grown

Inclusions form from the growth environment. Natural diamonds grow deep in the mantle over millions of years, with fluctuating temperature, pressure, and chemistry. That chaotic process traps other minerals, produces stress, and leaves complex internal textures. HPHT diamonds are precipitated from a molten metal flux under high pressure and temperature. CVD diamonds are built atom-by-atom from a carbon-rich gas in a thin-film chamber. Each environment produces characteristic defects, inclusions, and strain patterns—like fingerprints of origin.

The tools and lighting I actually use

- 10× loupe and a darkfield microscope (20–60×) for inclusion form and relief.

- Fiber-optic light to trace growth lines and fine graining.

- Crossed polarizers (or a polariscope) to read strain (anomalous birefringence).

- Strong magnet (neodymium) to test suspected metallic inclusions.

- LW/SW UV lamp for fluorescence patterns (supporting evidence, not proof by itself).

Natural diamonds: the inclusion signatures

Look for complexity and variety. Natural stones usually show a mix of inclusion types and stress features that do not sit on neat planes.

- Mineral crystals of other mantle species: tiny garnet, olivine, chromite, or sulfides. They appear as well-formed crystals (often octahedral or rounded) with non-metallic luster. Why it matters: in a mantle melt, foreign minerals get trapped; CVD has no such minerals present, and HPHT flux inclusions are metallic, not silicate or oxide crystals.

- Pinpoint clouds that form irregular, cottony patches—not strictly planar. Why: natural nitrogen aggregation and micro-inclusions develop over eons in diffuse swarms, rather than in single deposition layers.

- Feathers and cleavages that follow {111} planes, sometimes stepped or “gnarled,” with faint iridescence. Why: tectonic stress and later healing events create complex, branching breaks in natural crystals.

- Twinning wisps—wispy trails of pinpoints, clouds, and minute crystals along internal twin boundaries, especially in stones cut from twinned crystals (macles). Why: growth reversal planes are common in natural diamond crystals.

- Strong, chaotic strain under crossed polars, often “tatami” or cross-hatched patterns. Why: natural growth and deformation lock in uneven stress; lab stones are typically much more uniform.

- Girdle naturals with trigons (etched triangular pits) if any original skin is left. Why: natural octahedra etched by fluids show trigons; cutters sometimes leave a natural on the girdle as weight-saving. Lab crystals rarely provide a reason to leave naturals, and their surface etching looks different.

HPHT-grown diamonds: what gives them away

Think metal and geometry. HPHT crystals grow out of a molten metal flux (typically Fe-Ni-Co), often in multiple sectors of a cuboctahedral seed.

- Metallic flux inclusions: highly reflective black or silvery specks and platelets, sometimes rounded “beads.” They often blink brightly when rocked and may be magnetic. Why: droplets or fragments of the flux become trapped during rapid crystallization.

- Sector-dependent inclusions and color: clouds or color zoning confined to geometric growth sectors (cube vs. octahedral). Under magnification, boundaries can look straight and polygonal. Why: different sectors incorporate impurities at different rates in HPHT growth.

- Relatively low, even strain under crossed polars compared to naturals; patterns may appear sectorial rather than chaotic. Why: controlled pressure and temperature reduce deformation.

- Fluorescence “shapes” that mirror growth sectors (crosses, octagons) under UV, sometimes with a chalky character. Why: impurity uptake by sector produces geometric fluorescence maps. Use only as a supporting clue.

CVD-grown diamonds: the planar, layered look

Think layers and graphite. CVD builds diamond in horizontal sheets on a seed plate, then repeats.

- Planar growth lines parallel to the table: faint, evenly spaced bands or striations you can trace with a fiber-optic light from the side. Why: each deposition cycle adds a thin layer, creating a stack like pages in a book.

- Plate-like or sheet-like clouds confined to those layers rather than diffuse, 3D swarms. Why: defects concentrate at specific growth steps.

- Dark graphitic clusters or platelets, often along layer boundaries or near edges. They look inky rather than metallic and are not magnetic. Why: CVD can precipitate sp2 carbon (graphite) when conditions drift.

- Low overall strain but with banded patterns tied to the layering, rather than the chaotic tatami seen in naturals. Why: the process is orderly, with stress localized at layer interfaces.

- Uneven or orangey-red SW fluorescence with potential afterglow in some CVD stones (phosphorescence). Why: vacancy-related defects common in CVD can luminesce differently. Again, this is a secondary clue.

“Too clean” explained

People say lab diamonds are “too clean” because many are grown and selected to maximize clarity. In practice:

- Lab stones often show very few inclusions overall, and those that do appear are consistent with the method (metallic beads for HPHT, planar bands for CVD).

- Natural diamonds can be internally flawless, but most show a mixture of inclusion types and non-planar distributions.

This doesn’t mean a flawless stone is necessarily lab-grown. It means that when a stone is unusually featureless, I look harder for the subtle method-specific signs: sector geometry (HPHT), planar banding (CVD), or the rich, irregular “messiness” of nature.

Quick field checklist (10× to microscope)

- Suggests natural: mixed inclusion suite (non-metallic crystals, irregular clouds, feathers), twinning wisps, chaotic/tatami strain, trigons on a girdle natural.

- Suggests HPHT: tiny metallic reflectors; magnetic response; geometric sector zoning; sector-shaped fluorescence; low, even strain.

- Suggests CVD: parallel growth layers; planar clouds; graphitic specks or plates; banded strain; table-parallel graining.

Why these clues are reliable

- Causation, not coincidence: Each pattern comes directly from the physics of growth—melt vs. gas, layered vs. sectorial crystallization, impurities present or absent.

- Multiple, independent lines of evidence: When two or three of the above features align, the probability of a correct call rises sharply.

Pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Don’t rely on a single clue. Some naturals are Type IIa and very clean. Some HPHT stones lack obvious metallic specks. Some CVD stones are post-growth treated to reduce visible defects.

- Don’t confuse treatments with origin. Laser drill holes (straight channels to a dark pit) and fracture filling relate to clarity enhancement, not whether the diamond is lab or natural.

- Needles vs. metals. A shiny, mirror-like speck that flashes and is magnetic points to HPHT. A translucent needle or non-reflective crystal is more consistent with natural.

- Fluorescence is suggestive, not decisive. Use UV only to support what you already see in the microscope.

When to escalate to lab testing

If the stone is high value or unusually clean, send it for instrument testing. Here’s why:

- FTIR can determine diamond type (Ia vs. IIa/IIb). Most CVD and many HPHT stones are Type IIa; most natural diamonds are Type Ia. This is a strong filter, not absolute proof.

- Photoluminescence and UV-Vis reveal defect centers (like NV, H3, SiV) and their distributions, which are diagnostic of growth method.

- Advanced imaging (DiamondView-style) shows sector geometry and growth fronts in amazing detail—excellent for HPHT/CVD calls.

Buying advice: questions to ask and what to look for

- Ask for the grading report specifying “laboratory-grown” or “natural.” Major labs label origin clearly.

- Under the loupe, look for either: a healthy variety of natural inclusions (crystals, irregular clouds, feathers), or the neat, method-specific patterns described above.

- Check for metallic specks and try a magnet if you suspect HPHT. No attraction ≠ natural, but attraction + reflectivity is strong evidence for HPHT.

- Scan the profile with a fiber-optic light. Parallel banding pointing to the table suggests CVD layering rather than natural graining.

Bottom line

If your diamond shows a mix of non-metallic crystals, irregular clouds, occasional feathers, chaotic strain, and maybe a girdle natural with trigons, you are very likely looking at a mined stone. If instead you see metallic sparkles and sector geometry, think HPHT. If you find planar banding parallel to the table with graphitic specks and neat, low strain, think CVD. The reason is simple: the inclusions mirror the way the diamond grew. Nature is messy. Machines are tidy. And that difference is written inside the stone.

I am G S Sachin, a gemologist with a Diploma in Polished Diamond Grading from KGK Academy, Jaipur. I love writing about jewelry, gems, and diamonds, and I share simple, honest reviews and easy buying tips on JewellersReviews.com to help you choose pieces you’ll love with confidence.